Imagine a state where everyone prospers. Women and men dress up, play sports, laugh, talk, joke, tease each other and play games. Great craftsmen use the most vivid colors to depict the beauties of nature on the walls, create ceramics and jewelry and process metals with mastery.

Imagine people who love the sea and use their ships to travel to the most incredible countries. There they trade in oil, wine and works of art. They build strong friendships with new people they meet.

Imagine people that know no fear, that build no walls around their state, that are united and share everything they acquire, under the guidance of their righteous King. Everyone, regardless of their place in society or their origins, dine together, and the children are educated equally, upon expenses of the state. The least wealthy among them, reside in small villas.

They worship mother nature, love animals and respect flora, wherein they look for secrets to promote their health. They constantly seek to evolve, improving their lives, as well as the lives of those around them, through the practice of arts, sciences and inventions.

At every opportunity, they dance and enjoy life, together.

At the end of the third millennium BC, the most advanced ancient civilization in Europe, the Minoan civilization, was established in Crete. It has passed on to us findings in the fields of art, architecture, religious worship, entrepreneurship and social administration, which testify to a social, economic and cultural level that had been both innovative and unparalleled, yes… unparalleled to this day.

The Minoan world was a joyful world, which had set its priorities correctly. The dominant emotion was the joy of being, creating, loving, evolving.

It is verified that life has existed in Crete since the Neolithic era, between 6.000 and 5.000 BC; there are indications though, that the island was already inhabited from the Mesolithic or the Late Paleolithic period (8.000 BC). During the Late Neolithic era (3.500-2.800 BC), people would inhabit the whole island, moving towards the coast, even the surrounding small islands. They led a peaceful lifestyle, were productive and worshipped the female goddess of fertility, as shown by a series of figurines found during excavations.

Photo: Clay Female Figurine, Kato Chorio Ierapetra, Middle to Late Neolithic Era (5.800- 4.800 BC), Exhibited in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion. (Photo credits: Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0)

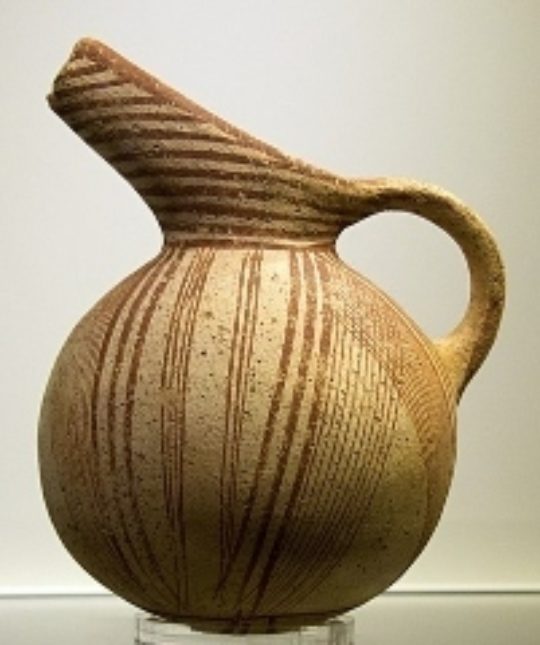

Within the period 2.800/2.600 – 2.000/1.900 BC, also characterized as the “Prepalatial” or “Early Minoan” period, ceramic art would evolve, incorporating new methods and decorations of nature imagery. Settlements are traced in southern, central and eastern Crete, where burial architecture would also develop. [7] Among the grave goods and offerings were jewels, showing the advanced metalwork and microsculpture of the time, as well as seals bearing symbolic representations.

Photo: Round – bottomed basin bearing clusters of diagonal lines made of red paint, Saint Onoufrios 2.600 – 1.900 BC. Exhibited in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion. (Photo credit: Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0)

To this day, we do not know whether the first inhabitants of the Neolithic era were indigenous or settlers. Their origin remains an unsolved mystery. Around 2.600 BC, at the dawn of the Bronze Age in Greece, migrating tribes would arrive in Eastern Crete, probably from southwestern Asia Minor, the Aegean Islands and Central Greece, that was then inhabited by prehistoric Greek tribes. With them, they brought the knowledge of the processing and use of copper, especially of the copper and tin mix, called brass, or bronze. Thus, in Crete, a federation of tribal states was created, all or most of which consisted of Greek tribes. [2]

"“In the middle of the open Sea there lies an island, Crete,

which is beautiful, fertile, surrounded by sea.

It has countless inhabitants and ninety cities.

Every people there speak their own language.

The largest city of the island is Knossos,

where Minos,

who would have a discourse with Zeus every nine years,

was King.”

Homer, Odyssey. [4]

From 2.100 to 1.560 BC, during the Middle - Minoan period, Crete was thriving. Around 1.900 BC, in the Protopalatial (old – palace) time, large and beautiful palaces were built in various cities of Crete, constituting administrative centers that were governed by local rulers - princes. Some of them, the largest ones discovered, were Phaistos, Kydonia, Gortys, Mallia, Zakros and, of course, the seat of the confederation and center of government activities, the majestic Knossos, palace of the legendary king Minos.

Around 1.700 BC, palaces, as well as large houses and settlements, probably destroyed by a major earthquake, were rebuilt immediately, even more majestic. The ruins of the second phase palaces (Neopalatial period) were discovered in archeological excavations.

Fun Fact: The architectural know – how of the ancient Cretans is unparalleled. Knossos alone, consisted of 5 floors and about 1.500 rooms! The palaces also disposed of anti-seismic protection and a perfect hydraulic and sewerage system with special bath rooms.

The Ruler of the entire island, the King with a thousand faces, was not one person. The name “Minos” was a king’s title such as e.g., the “Pharaoh”, attributed to all persons who would acquire a royal status in the Minoan era. The first Minos, however, according to the legend, was born from the union of the God Zeus and Europe, same as his brothers, Radamanthis and Sarpidon.

Photo: Silver tetradrachm of Knossos with the head of Minos and a diagram of Labyrinth routes.[13]

The next husband of Europe, Asterios, king of Crete, adopted him and Minos succeeded him to the throne. He married Itoni and had Lycastus, who in turn succeeded his father to the throne and married Ida, with whom he had Minos II, creator of the vast naval power that would reign over the seas. [2]

Fun fact: The memory of King Minos’ reign was preserved in various locations of the Greek maritime space, along with the labyrinthine architecture of the Minoan palaces, as conveyed by the myth of the Ancient Greek Mythology Theseus and the Minotaur.

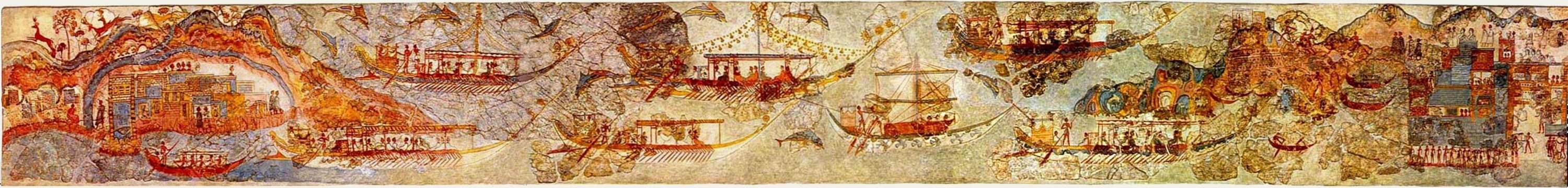

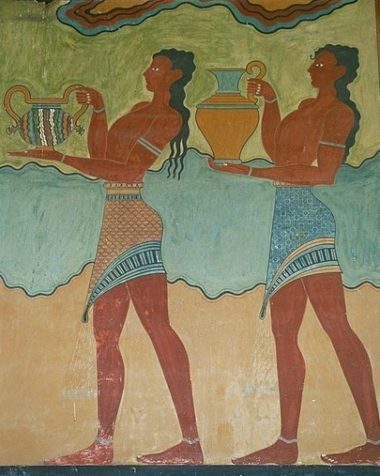

The Minoans were good sailors. They made the best of the geographical position of Crete and of its natural advantages. They built centers and ports in the most suitable parts of the island and colonized the surrounding smaller islands. They built many boats in sophisticated shipyards and became successful merchants. Fearlessly, they would cross the seas, to bring to the island abundant raw materials from distant lands, such as copper, tin and other metals, ivory, precious stones and timber, while at the same time selling wine, oil, pottery, textiles, tools and jewelry. [4]

Photo: Minoan Ship, a replica of a 17-meter-long prehistoric rowing boat of the 15th century BC. (Photo credits: Martin Belam, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The creations produced in private and palace workshops were traded throughout Asia Minor, Cyprus, Syria, Egypt, Sicily, even Spain. They developed friendly relations with the other people living around the Mediterranean basin and had an influence on Egyptian art and the lifestyle of Mainland Greece, where the Achaeans had settled.

They would record their accounts and transactions in accounting books. They used a decimal number system. It is fascinating to see their daily routine come to life through the pre-alphabetic forms of writing, on the clay tablets that were found.

Fun fact: They even carried liquid products in special amphorae. They would block their mouths with a piece of clay which was sealed with the trademark of each producer.

Image from the book: "The palace of Minos: a comparative account of the successive stages of the early Cretan civilization as illustrated by the discoveries at Knossos" by Evans, Arthur, Sir.

Minos used his fleet to dominate maritime trade and transport, long before the appearance of the Phoenicians. He dealt with piracy in the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean. Apart from the Minoan State, he established many trade centers and colonies in mainland Greece, Asia Minor, the Black Sea and elsewhere. In fact, as findings reveal, the Minoan voyages may have ended up even further away than we had imagined. The merchant fleet of the Cretans, at the peak of its domination, had established the “Minoan Thalassocracy”.

Photo: Part 1 of the Ship Procession Fresco, Cycladic Port, Akrotiri Thira.

Fun Fact: The wooden walls: The Minoan cities had no protective walls. This is proof not only of their peaceful attitude, but also of the strength and security they had thanks to the countless “Ships, ships, ships!”[4]

In the beginning, the Minoans (2.000 - 1.700 BC) would use drawings that represented objects and symbolized words, from which they would convey the first syllable. This script was called Cretan Pictographic (or hieroglyphic) and, according to many researchers, it was lexical syllabic.

During that same period and later on (1.850 – 1.450 BC), they used another type of script, which, apart from ideograms, also comprised characters of a more “linear” form. Archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans named it Linear A, and it was mainly found on clay tablets and seals. Linear A has not been deciphered and constitutes a great archaeological mystery. Its ideograms lead us to the conclusion that the tablets were mainly archives, lists of people and goods, even worship texts.

It is considered the forerunner of the deciphered Linear B (1.400 – 1.200 BC), a writing of administrative use created by the Mycenaeans of the mainland, based on Linear A and the Pictographic writing. [12] Linear B was deciphered by the linguist and architect Michael Ventris in 1952 and is the first Greek writing of the European civilization. The two linear writings have common elements, as well as significant differences.

Image: Comparative table of elements of Cretan Pictographic, Linear A and Linear B Writing, from the book: "The palace of Minos: a comparative account of the successive stages of the early Cretan civilization as illustrated by the discoveries at Knossos" by Evans, Arthur, Sir.

Fun Fact: We can see the Cretan Pictographic Minoan writing, or Cretan Hieroglyphics, seal - imprinted on a round plate of baked clay, the Disk of Phaistos, which is the first form of printing. To date, no one has been able to decipher it. It is said that there is a religious hymn on its A side, and probably the first mapping, with place names and the symbol of Crete, on the other side.

Image: Disk of Phaistos, view A. (Photo Credits: C messier - CC BY-SA 4.0)

The cities of Crete were united in a loose confederation. The system of government was monarchic and centralized, with King Minos as the ruler and Knossos as the metropolis, yet there was no tyranny. The cities were semi-autonomous administrative centers, with their own settlements, palaces and rulers.

The Reign of Minos was not for life; according to tradition, every 9 years Minos would go up to the “Cave of Ida”, where he would receive written laws from Zeus himself. In fact, it is considered that, to extend the term of the monarchy, some kind of elections would take place, and that the succession of Minos was not strictly hereditary, but would also depend on the consent of the “ekklisia”, i.e. the people’s assembly, in the Metropolis of Knossos.

The King was the supreme ruler, high priest and head of the legislature and judiciary. Around him, there were many high priests with religious and administrative duties, as well as officials and bureaucrats who handled private and state affairs. These complex tasks required a constitutionally organized state with laws, a sophisticated writing system, and administration. [2]

Fun Fact: According to Plato, Minos entrusted the implementation of the laws in Knossos to his brother Radamanthis, an excellent legislator and judge. For the rest of Crete, he appointed the mythical giant Talos, the first robot in history, made of copper, which looked like a huge man on the outside. Talos was so fast that he could traverse Crete 3 times in a day! He is often depicted with wings on his shoulders.

In Crete, despite the organization of people in cities, there was no class stratification nor privileges reserved for those in power. Successful trade, the productivity of the inhabitants and the administration of the state by Minos, as if he were the CEO of a company, led to wealth, which was generously returned to the citizens. The state would regulate the production and collection of goods in warehouses and took care to ensure their fair distribution to the entire population, so that no one were deprived, at least of what would be necessary for their survival. Thus, the phenomenon of social equality appeared in the world for the first time. [2]

The power, financial administration and wealth of Minos did not hinder private initiative and financial freedom. Ancient Cretans could operate private workshops, cultivate the land, trade, be sailors and generally evolve in any way they wanted.

Fun Fact: Nothing brings people closer than sharing the same table. In order to prevent the greed and envy that could possibly develop among citizens due to financial freedom, the law provided for the mandatory dining in state-funded meals, the so-called “andreia”, where both women and children would also participate. By discussing at the same table, the Minoans resolved their differences as equals, became friends, and learned to work together and plan their common future.

The institution of slavery in Minoan Crete was different from that of later years. Here, slaves would have the same rights as their masters and would only abstain from military exercises and the possession of weapons (Aristotle, Politics). The transition to the regime of individual, political and financial freedom, although there is no evidence regarding its exact appearance, is placed around 2.200 BC, that is, during the first period of the establishment of the Minoan state. Freedom ensured that the goods belonged to those who worked to acquire them and not their masters. This change contributed to the financial and cultural miracle that was the Minoan state (Politeia). It was the first time that individual freedoms and rights, such as the freedom of economic activity, were granted to citizens of the wider European area. [2]

Fun fact: Everyone would attend events such as theatrical performances and sports games with their family and servants. Places with stands and areas for large gatherings existed in every city. Gournia was considered a poor area. Yet people there would live in houses of 4-6 rooms. Everyone led a good life.

Photo: Archaeological site of Minoan city in Gournia, peak 1.550 – 1.450 BC.

The peaceful coexistence, prosperity and progress achieved by the voluntary union of 90 cities, for the first time in world history, is called Pax Minoica. Through a common official language and script, freedom of religion, a unified socio-political status and legislation, as well as a new metric and number system, the decimal, which is even used to this day, the Minoan state was at the forefront, thanks to the power of unity.

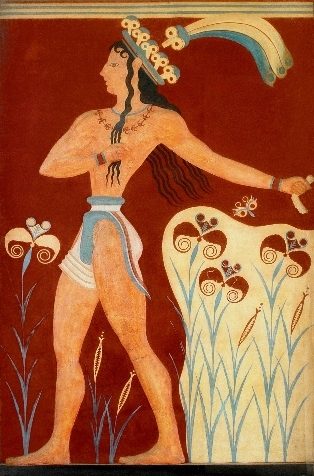

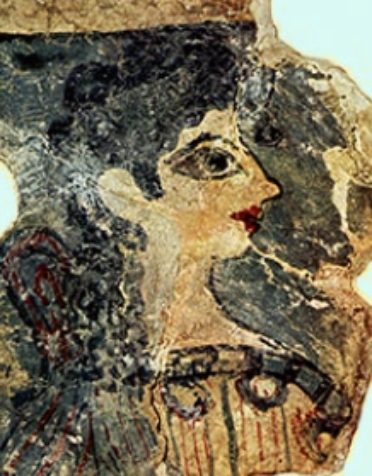

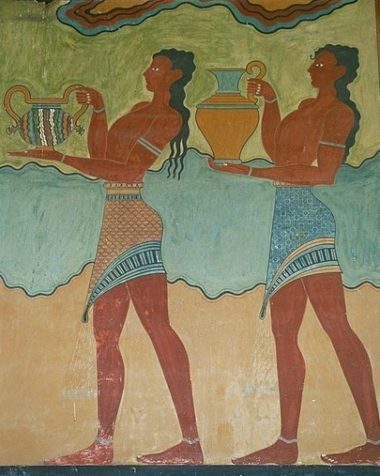

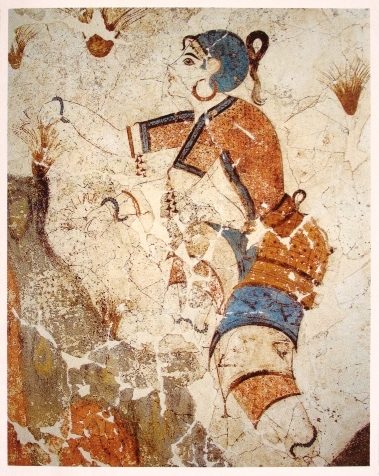

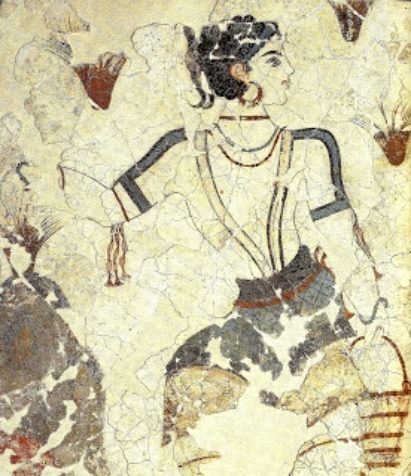

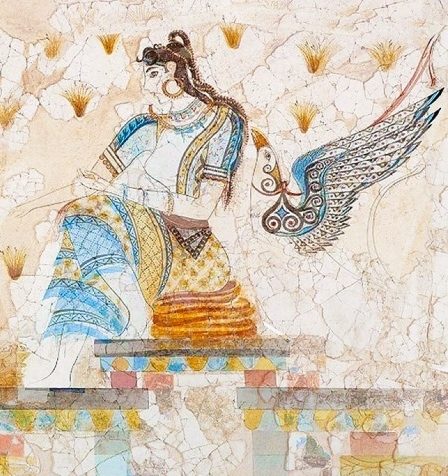

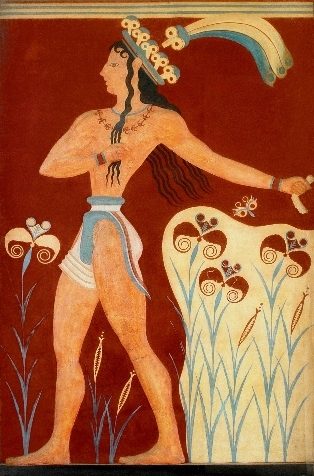

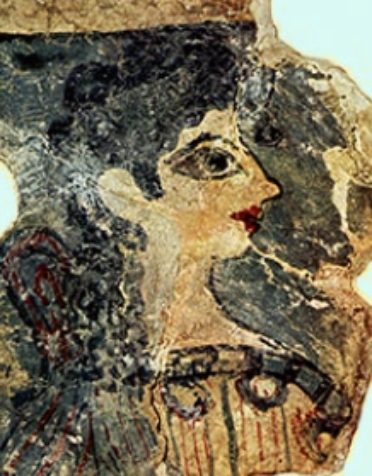

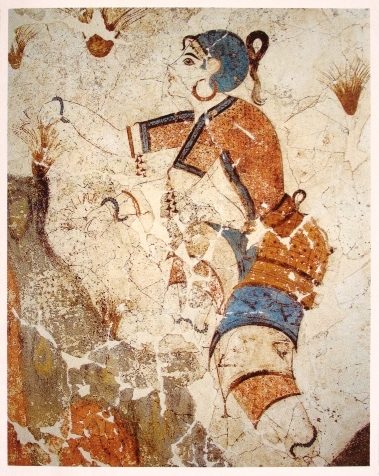

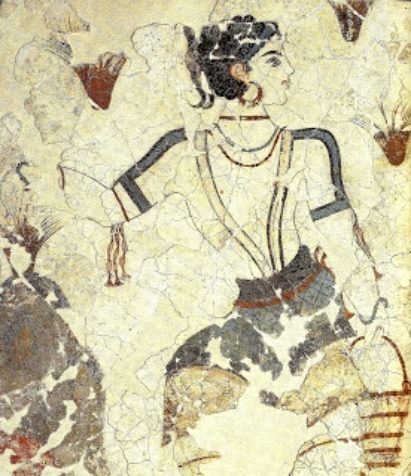

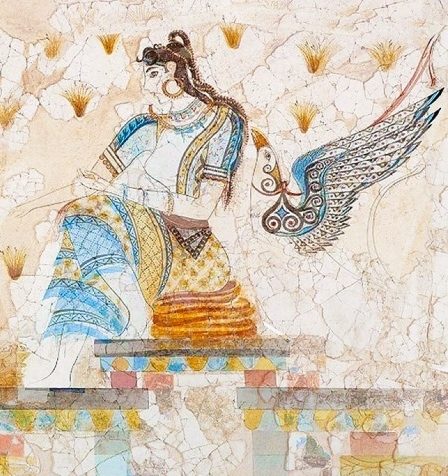

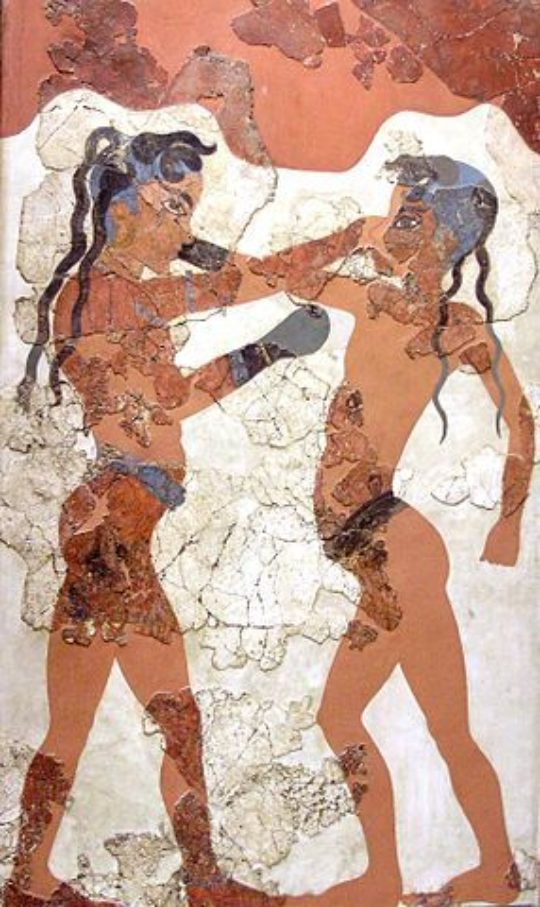

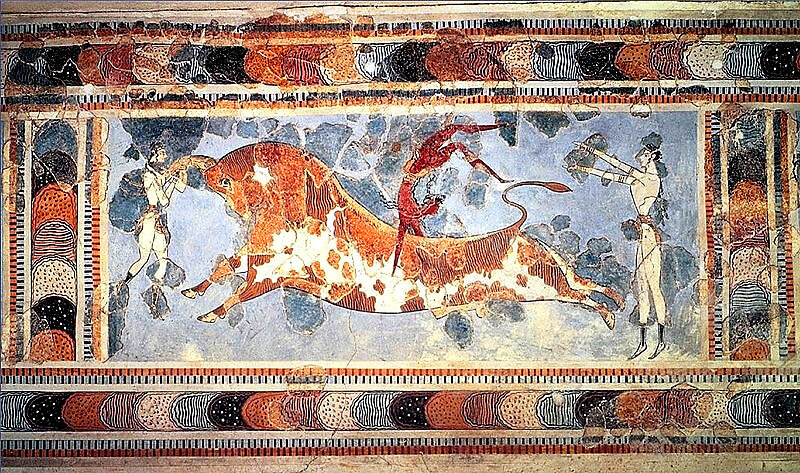

In Minoan Crete, women would equally participate in all events. Like men, they would take part in festivities, sports, hunting, even in bull leaping and boxing. They participated in political, religious, agricultural and economic life. They are often depicted in frescos, in a leading position or carefree, chatting joyfully at public events. Just imagine them, extra elegant, trading products, picking saffron flowers, performing devotional dances as Priestesses in religious ceremonies or cautiously playing chess (“zatrikio”) in the quiet living rooms of the palaces! Men were just as active, well-toned, with long hair, adorned with jewelry. They would wear simple but elegant girdles, combined with tight belts that would bring out their athletic bodies. Women and men were renowned for their style. [2,7]

It was the above information that has led many researchers to believe that the Minoan society was matriarchal. In our opinion, the point here is that it was based on the feminine qualities of mother nature. It was a society dedicated to the driving forces of love, affection and fertility, where no one felt the need to rule over the other, and everyone respected the pace of Mother - Earth. We can therefore say that it was a “motherly” society with respect for femininity.

The Gortyn Law Code of the 6th century BC is considered to be the oldest legislative text, not only in Greece, but in all of Europe, characterized by liberty and progressiveness. Both in the provisions of this legislative instrument, especially on the regulation of family and property issues, and in the naming customs of Asia Minor and the narratives of Herodotus, one can distinguish the high position of women in the social life of Crete and the relevant influence of the Minoan heritage.

In Minoan Crete, the children were dear to the adults and would dine with them in the “andreia”. They had a fair start in life, enjoying equality in education and opportunities. They would receive public and compulsory education, regardless of their sex, social origin and economic status, in groups called "ageles”.

They were taught martial arts, dancing, writing, odes and paeans, but also the laws that kept their state intact. Uniform education resulted in making the best citizens, in conditions of free competition and access to knowledge for all. [2]

Fun fact: The children would play many games familiar to us today, such as ball, jumping, road racing and board games with dice. A solid - gold chess (“zatrikio”) was found in Knossos, probably a game of noble children. [4]

Photo: Fresco from the prehistoric settlement of Akrotiri. It depicts two small children practicing boxing. National Archaeological Museum of Athens.(Photo credits: Marsyas (2007), CC BY 3.0)

Ancient Cretans loved to play sports. Plato mentions in his Laws (452, c, 9) that “the Cretans were the first to practice sports”. Frescos, vases and seal stones give us a lot of information about their preferred games. The participating athletes, women and men alike, are depicted as flexible and well-trained, with slim waists, strong limbs and well-formed muscles. Men are tan, wearing robes, tight belts, jewelry and sandals. Female athletes also wear girdles or bell-shaped skirts, with fitted waist – belts leaving their chest exposed.

Bull leaping (“Taurokathapsia”) was one of the most popular sports in Minoan Crete. In this game, athletes would perform spectacular jumps and stunts on the backs of horned running bulls.

Fun Fact: In his “Politeia”, Plato refers to sports in Crete with the phrase “the Cretans were the first to dismiss clothes” in sports. This is an innovative element in sports and culture, since feeling ashamed to practice sports naked, was a sign of barbarism, according to the author.[5]

Τα αθλήματα πιθανότατα αποτελούσαν μέρος του τυπικού μιας τελετουργικής μύησης (ενηλικίωσης) των νέων, είτε είδος θρησκευτικού θεάματος που διοργανωνόταν από το παλάτι, με μεγάλο κοινό και δημόσια βράβευση των νικητών. Κατά την παράδοση ο Μίνωας τίμησε τον Θησέα, όταν αυτός νίκησε τον Μινώταυρο, δίνοντας του δώρα και χρυσό για να επιστρέψει στην πατρίδα του. [5]

Wrestling, boxing and the combination of the two, the pankration, were also popular in Minoan Crete. From findings depicting sports, such as the steatite rhyton of Agia Triada, we have come to understand that there were specific moves involved and that the games were organized activities. They also enjoyed running, sphere and discus throwing and, being sailors, rowing and swimming. The so-called ring of Minos depicts a sacred ship carrying a double – horned altar, on which there is a rowing female figure. [5]

Image: Detail depicting a boxing scene, from the stone “sports rhyton” made of steatite, Neopalatial period, circa 1.500 – 1.450 BC, Agia Triada. Exhibited in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion.

Fun Fact: Cretans were considered as the best archers and javelin throwers. They participated in many battles of antiquity, according to Thucydides and other authors. Diodorus states that the Cretans had been taught how to practice archery by the Kourites.

Image: Seal stone depicting an archer with bent limbs, stretching the arch string. Agia Triada, “Villa”, Late Minoan IB period. [11]

The Minoans, being a joyful, warm people, loved festivals, singing and dancing, which were also part of their religious rites. This love remains very much alive to this day, as, in many places, after a religious ceremony, there are festivities and dancing outside the church. According to Homer: “Young women wearing soft linen dresses would go hand - in - hand with young men wrapped in well-woven robes. They would bear beautiful crowns on their heads and gold knives hung from silver straps. They would gracefully dance in one row, then form two rows, one facing the other”. [4]

Image: Clay dancing model, women dancing in a circle accompanied by a lyre, Palaikastro Sitia, Postpalatial period (1.400 BC)

With regard to the arts, the Minoans were totally inspired by nature. They would paint beautiful frescos in the palaces, with color harmony, playful dolphins, marine plants, octopuses and fish or gardens with olive groves, wild goats and partridges, palm trees and lilies, peacocks and monkeys. Smiling people in parties, daily chores or worshipping processions and games, along with mysterious motifs, would complete their world.

Through the introduction of the fast pottery wheel, pottery developed a lot from an artistic point of view. Cretan vases, either made of stone or clay, were used for the storage of oil, wine and fruits. They were also used as decoration or for ritualistic purposes. They were exported to many countries, famous for their beauty, adorned with images of nature, flowers, animals and plants.

Minoan vessel from Zakros, decorated in Marine Style, 1600-1450 BC. Archaeological Museum of Heraklion. Photo Credits: Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0

The “Kamaraika” vessels of the Middle Minoan period were renowned for their coloring and imaginative design. They were named after the cave Kamares of Psiloritis, where many of those were found. Some of them, due to their thin, egg – shell like walls, were even called “ookelyfa”. When they touch, they produce a sound similar to that of crystal!

Microsculpture and metalwork, using raw materials like gold, silver, agate and lapis lazuli, have given us works of art such as, seal stones, jewelry, ceramics and other samples of exquisite craftsmanship. In goldsmithing, the techniques were as advanced as they are today, with gold plates and sheets, gold-welding, wire-making and granulation. [7,11]

Minoan art presents life illustrations in naturalness, warmth and subtle sensitivity. This art is full of imagination and power, while there is no place in it for the fear of death, fellow human beings or the gods. The joy of life dominates it.[4,7]

Fun Fact: The palace of Zakros rhyton, made from rock crystal, 16 cm tall and 2 mm thick, has made researchers wonder about its making tech, as they seem unable to explain how prehistoric craftsmen had managed to give it such a detailed shape, which would only be possible today with the use of laser.

In Crete, the great goddess – Mother was greatly revered, influencing the whole life of the Minoans, from politics and artistic events, to economy and everyday life. People connected to nature, would cultivate their land and cross the seas for a living. They would ask the goddess to protect them and make the earth bear fruit and the seas calm. They would ask her to give them peace and fertility, by holding impressive religious ceremonies.

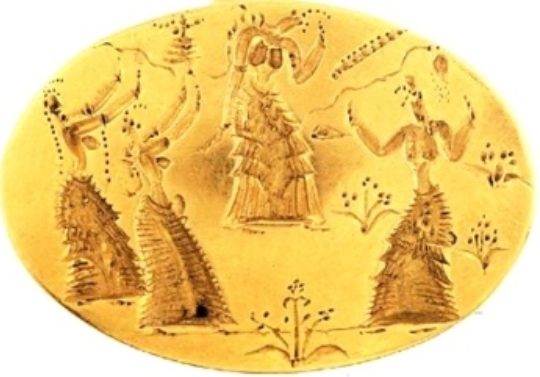

Image: Representation of Epiphany and ecstatic dancing of women in a flowered field on a golden ring (Tomb of Isopata Knossos, Neopalatial period, 1.600 BC)

The female snake - goddess, the female figures on the seal stones depicting worship scenes, the female figurines, they all represent the forms taken by the primordial Mother - Earth and highlight the motherly character of the Minoan religion, connecting femininity with the forces of life. [14] In illustrations, there was often a smaller male god of vegetation next to the goddess – Mother.

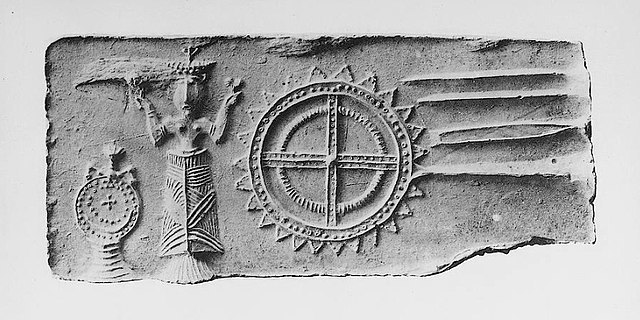

In religious content representations on seal stones, one can see zoomorphic or bird-like demons. The sacred olive tree, the double ax or “lavrys”, the bullhorns, the two-headed griffins in the room of the Throne of Knossos, are religious symbols. The Bull itself was considered a sacred animal.

Image: Minoan Snake Goddesses 1.600 BC, Knossos Palace

The representation of the sky was useful to the Minoans, who would consider it as a huge clock. Based on observation, they made great progress in astronomy. Applying the relevant knowledge, they knew when they were to do their farm work and could navigate in the seas. Special tools, created for this purpose, have been found, such as the Minoan Moulds of Palaikastro, also known as the first “analogue Minoan calculating machine” serving as a sundial, determining latitude and predicting each subsequent eclipse, based on the positions of the sun and moon in a geocentric system.

Did you know that ...the Minoans would monitor and plan pregnancies using the Tiganoschima (meaning: shaped like frying pans), the first portable pregnancy diaries, mathematically depicting planet conjunctions. They would lead their lives in complete harmony with nature, and built shrines and buildings that helped them locate the sun at certain times of the year, as well as the alternations of the seasons.[1]

The agricultural routine of the Minoans comes to life through their farming tools, the ancient olive mills and presses found. The Minoans taught the rest of Greece and the world how to systematically cultivate olive trees, vines and wheat. They also grew flax, saffron, legumes and vegetables. They would produce wood for construction and for the building of the Cretan fleet, from mountain oaks, firs, and cypresses. [7] Through observation and experience, they discovered the healing and cosmetic properties of plants.

Image: Seal representing a female figure wearing a ruffled skirt and a chain around her neck. The second figure wears a long garment covering its whole body, with ruffles on the bottom, an overcoat on the shoulders and a hat that looks like a cap. In her bent hand, she holds a tool (an ax or pickaxe), which she carries on her shoulder. Find of Kato Zakros, Late Minoan IB Period. [11}

Hunting, livestock farming of pigs, goats, cattle and sheep, as well as beekeeping, were daily activities. The same goes for grinding wheat, spinning and embroidering. For agricultural work, they would utilize oxen and donkeys. The Minoans coexisted and were friendly towards animals.

Image: Seal representing a female figure in a ruffled skirt, sitting on a stool feeding a goat. Find of Kastelli Chania, 10 Katre Street, Late Minoan IB Period.[11]

Around 1.500 BC, a second disaster razes all the Minoan centers to the ground. From how the palaces look now, it seems that they fell into ruins, burning down. Historians had developed the hypothesis that the people of mainland Greece invaded Crete, looted and burned the palaces. However, as confirmed by excavations and natural sciences, the cause was a natural disaster. It seems that, at that time, there was an eruption of the volcano of Thira (Santorini), during which lots of volcanic material (pumice) and sulfur were ejected in all directions, at a distance of 20 - 30 km, while huge tidal waves (tsunamis) swept north Crete and flooded half the island. Due to the fires and earthquakes that followed, almost every trace of life turned into ashes. Thus, the most brilliant palaces ever built on Greek soil were destroyed. [4]

Interesting fact: “The eruption of the Volcano of Santorini was an eruption of a super volcano level that affected the climate throughout the northern hemisphere. It caused a sharp drop in temperatures and the rains became much more acidic. This was followed by a series of climate changes that led to a period of severe drought, which were to alter the economic and social balances of the wider Central Europe”. [6]

From about the middle of the 15th century BC (Late Minoan period or Late Palace period), the Mycenaeans of mainland Greece, progressively coming over, managed to dominate Knossos. After the destruction of Thira, around 1.400 BC, the Achaeans of the Peloponnese would arrive in successive waves. Around 1.380 – 1.350 BC (Post Palace), the palace of Knossos was completely destroyed, never to be reconstructed. The cities of Crete remained numerous, but the composition of the population changed. The houses would now be similar to those of Mycenaean Greece, the sea empire would end and trade would pass over to the hands of others. In the 12th century BC, the Minoan civilization would come to an end. In 1.100 BC, the first Dorians would conquer the island without resistance. [4]

With the arrival of the Dorians, most of the settlements were abandoned, and the inhabitants who would not yield to the new settlers moved to inaccessible mountainous areas. Seeing the form of their hitherto known world changing, the peoples of Eastern Crete self-organized on an equal and democratic basis, creating new structures in the mountainous hinterland. They were to overcome the collapse with nature itself as their ally, creating new tools and works of art, while processing new raw materials. [6]

Eight centuries later, Homer would mention the Eteocretans among the peoples of Crete that had now been colonized by the Dorians. [7] They were also mentioned by Diodorus of Sicily and Strabo. They were considered indigenous (“eteos” means true, real, genuine) and descendants of the Minoans. Eteocretans left written records in a language that has not been translated to date and may have originated from the Minoan Linear A. Until, however, there is an acceptable decipherment of Linear A, the language shall remain unclassified. We have very little historical data for the period 1.100 - 300 BC, but the excavations in the areas of Vrokastro, Karfi, Kavoussi, constantly help us to complete the data and unlock knowledge about that time.

Of course, the spirit of the Minoans lives and reigns in the Cretan folklore tradition. It reaches present days like a beacon of light, offering answers in shipping, agriculture, art, business, nutrition, entertainment, dancing and singing. The fair distribution of wealth, coexistence and self-sufficiency, survive within the institution of family. Rational management and respect for nature become obvious in agricultural practices. Modern Cretans are still interested in shipping, and in the exchange of ideas through tourism, science, art and trade.

The practices of the Minoans are alive in the relationship with the land, the sea, in the relationship of people with each other. It is a philosophy of life that we have inherited, not just as Crete, but as humankind. A Historic Good.

The Minoans have started their journey all over again, this time to unite the whole world through friendship and good food. Because joy, solidarity and desire for constant evolution, are unstoppable!

1. Tv – show “Antitheseis” (“Contrasts”) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9_RtTk7_ziI Μ. Tsikritsis - Minoan Civilization - Astronomy 13.02.2015

2. The Minoan Multiracial State as a Model for the European Union. Christos Theof. Salatas, Lawyer - Athens 2007, Athens Bar Association.

3. Minoan Herbs and Medicine, Dr Minas Tsikritsis, Heraklion 2019

4. History book of 3rd Class of Primary School 1991 and 1st Class of high school (Textbook Publishing Organization) 1977

5. Minas Tsikritsis stigmes.gr

6. “Archaeology, The most important finding will not come from the earth”, “atechnos” publications Vera Klontza Giaklova - Manolis Klontzas

7. Website http://www.kairatos.com.gr/

8. Website of the Minoan Culture and Writings Association https://minoikigrafi.gr

9. Website: https://sites.google.com/site/imakrhtikoi/toponymia

10. “Cretans”, Roots of the Greeks, Anthropogeography of Greece, Pegasus Publications

11. “Neopalatial Palace Seals with representations of Human Figures: Contribution to the Study of the Administrative System” Tsagaraki Evangelia, Doctoral Thesis, Department of History and Archaeology, A.U.Th., 2005

12. Syllabic and pictographic writing systems in the Minoan civilization 200 – 1.200 BC (Link)

13. Adamantios (Makis) G. Krasanakis, “Monetary History and the Ancient Cities of Crete and their Coins”, 2nd Edition. “ATHENS” Publications Agia Paraskevi Attica 1985

14. Website: https://www.sch.gr

From the dark labyrinth of Minos, to the sun! A tale about seeking freedom.

Read More

The fast copper giant, entrusted with the observance of the law and the pro

Read More

The fourth largest palace of Minoan Crete, base of the Fleet, trade center

Read More